The Lord’s Last Bastard Descendant

REVIEW: Joshua Cohen’s The Netanyahus is a dream, but who is the dreamer?

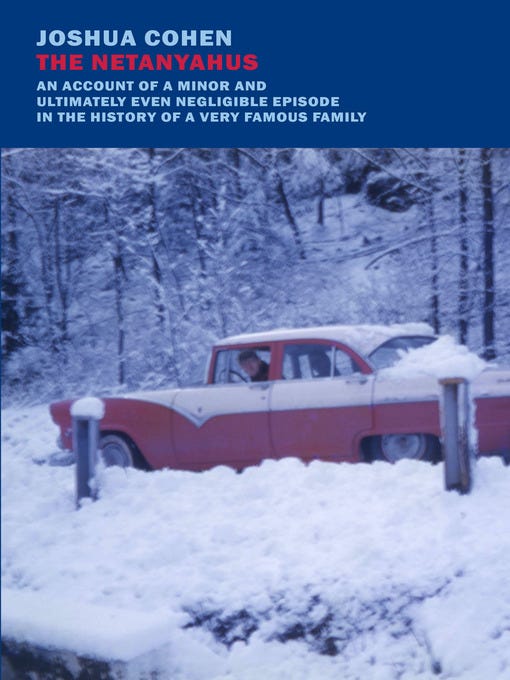

Snowbound and at home in this the first month of 2022, year two of what is still meant to be our new Roaring Twenties, it is appropriate that we begin with a book about a visit during a snowstorm, even if there’s no snow on the ground outside (look outside — is there?). The book is called The Netanyahus, the author is Joshua Cohen, the story is from one apparently told to Cohen by the now-departed Harold Bloom about the time he hosted Benzion Netanyahu, the father of future prime minister Benjamin, for an interview for a faculty position at his university.

Though the two men were from different academic disciplines — Bloom a literary critic, Netanyahu an historian of the medieval period — Bloom just happened to be the only Jewish faculty member and this was some time in the mid-twentieth century, so his administration felt he was the obvious choice of host, that he would be able to make Netanyahu the most … comfortable. And Bloom quickly found that it was not just Netanyahu but his wife and three sons too who were coming to visit. Hijinks ensued, etc., and thus we have the book The Netanyahus starring the fictional “Ruben Blum” hosting the real life Netanyahus at the fictional Corbin College in 1959, and it is a dream that won’t leave.

It won’t leave me, that is, because it gives the reader what feels like second sight, of a kind that permits us to see arcane images of a hidden present projected through a dream of the past. It is a dream, though maybe this is a tricky thing to say, but only because the book itself is so tricky. It appears to be one thing but is really another. Call it a dream and you resolve any gripes about historical accuracy, or peculiarities of the writing style, or puzzling over how the characters are represented.

The dream feeling sets in slowly. At the start, the narrator Ruben Blum introduces himself forthrightly, endeavoring to give the reader some context for apprehending him. He seems alive and real, and he tours us through scenes with vivid period details — old television sets, cocktail hour faculty meetings, secretaries and on and on. But somewhere along the way these details and the people amidst them seem to lose their breath. They shrink and harden into unreal fragments, leftover junk, and we drift out of the living past and into a mere catalog of it. Ruben Blum starts to seem not a man at all, and instead he is all context, and a dead context at that. He is an anxious dream image of a deflated past, a sitcom script memory of a man, one whose life and language and culture are already gone. We are no longer visiting at his home but rifling through the boxes in the basement, surveying what’s been discarded. But they are not solid things — when we reach to touch them they slip away from us, and we find we are dreaming.

Perhaps Blum is dreaming too, but he doesn’t know it, and he lapses from character to mute signifier as the book proceeds. In the end he comes to represent just the one thing — the assimilated American Jew — and rather blandly. His wife refuses his sexual advances, his daughter becomes fully alien to him, and Netanyahu, like an uncanny mocking daemon or devil come to visit, sees him for the empty vessel he is. In fact it is Netanyahu himself who finishes Blum’s long emptying. He merely had to arrive, and his and his family’s presence overwhelm everything in Blum’s life.

A memorable metaphor is introduced of a twofold assimilation simultaneously occurring in different parts of the world in the middle of the twentieth century, one for Jews in the new state of Israel, one for Jews in America —

Just about a decade prior to the autumn I’m recalling, the State of Israel was founded. In that minuscule country halfway across the globe, displaced and refugee Jews were busy reinventing themselves into a single people, united by the hatreds and subjugations of contrary regimes, in a mass-process of solidarity aroused by gross antagonism. Simultaneously, a kindred mass-process was occurring here in America, where Jews were busy being deinvented, or uninvented, or assimilated, by democracy and market-forces, intermarriage and miscegenation. Regardless of where they were and the specific nature and direction of the process, however, it remains an incontrovertible fact that nearly all of the world’s Jews were involved at midcentury in becoming something else; and that at this point of transformation, the old internal differences between them — of former citizenship and class, to say nothing of language and degree of religious observance — became for a brief moment more palpable than ever, giving one last death-rattle gasp.1

Most literally, the meeting of Blum and Netanyahu signifies these two populations confronting each other after a decade of transmutation, and so they are representative figures in a meditation on the Jewish diaspora and its ongoing history. The book is of course deeply concerned with these matters. But if you read it solely in this literal sense, you miss the forbidding allegorical power that comes through in the force of its language and the teasing quality of its narration. Chapter by chapter, we seem to halt at some revelation never disclosed. They are curtailed, these enigmas, these abbreviated dreams. They seem ready to elaborate themselves and then unexpectedly sharpen into an anti-climax of ghostly sense experiences. They mesmerize us with terse images — shoes like horses’ lips, the stink of burning meat, a gallery of Blum’s ancestors with fire coming out of their mouths2 — that stick like the stubborn riddles of dreams.

“Dreams are involuntary”, Blum says,

Every tradition believes this, from the neurological to the numinous. Some dreams are held to be prophecy, while others are held to be nonsense, which is prophecy yet unmanifest, but all dreams are to be regarded as forced upon us, even those we have while waking — those waking dreams indistinguishable from yearning …3

To straddle your book between prophecy and “nonsense, which is prophecy yet unmanifest” is to produce a strange effect indeed, and this book works on you afterwards, like dreams do. If it is a waking dream indistinguishable from yearning, then it knows what it yearns for is no longer reachable. If it is partly a dream of impotence and decline, then it makes us afraid that the impotence might be our own, that it’s already here or coming soon.

But we are also fascinated with our disconcerting by the foreign visitor. Netanyahu is, as Harold Bloom would have put it, scandalously intelligent. All those around him are dwarfed in his presence. His erudition is vast, and he bites like a viper. He is conversant with all relevant fields of knowledge the interviewing faculty attempt to baffle him with. He dominates every conversation, every context. He sees through people instantly, and does not doubt himself.

As a rightwing ideologue, tyrannically resolute and singleminded, he might be taken as representing certain strongman political figures in our contemporary landscape. (There is more to say here). But when we meet Netanyahu we see quickly that, though a zealot, he is no buffoon, and his powers are irresistible, at least amidst such gutless company. No intelligence in the book stands to match him, and so he takes it over for himself.

What would you or I do if met with such a personality? Is there anything in our empty twenty-first century hearts that could meet his judgment or compare to the passion he has for his cause? What might we say, in response to all that diabolical eloquence?

Ah, but what did the real Harold Bloom say, back in the real 1959, or whatever year it was, if it even happened? His fictional stand-in Ruben Blum has little of Bloom’s intellectual force, or erudition, or passion, or even wit. Blum, like a faded Woody Allen avatar, might be called a minor wit, while Bloom is a major one. Blum, it seems, is written almost to embarrass Bloom. He briefly mentions his failure as a poet, submitting work to poetry journals and receiving rejections.4 He says of the academic discipline to which he’s dedicated his career:

Though my initial focus was on the economics of the pre-American, British Colonial period, my reputation, such as it is, was made in the field of what’s now referred to as taxation studies, and, especially, from my research into the history of tax policy’s influence on politics and political revolutions. To be sure, I never much enjoyed the field, but it was open to me. Rather, the field didn’t exist until I discovered it, and, like a bumbling Columbus, I only discovered it because it was there.5

He bumbles into his life’s work. He even says:

Don’t get me wrong: I’m proud of these achievements, or I was trained to say and even to think I was proud of them, mostly because each notch on my ever-expanding accomplishment-belt was supposed to bring me farther from my origins — as Ruvn Yudl Blum, b. 1922 in the Central Bronx to Jewish immigrants from Kiev …6

A man who consciously fled from his own Jewishness, whose

incipient bent for the humanities, and for literature in particular, was straightened out by various pressures (parental, practical) in column-style, so as to better arrange a career in sums.7

How fair this is to the real Harold Bloom’s personal life, particularly in regard to his Jewishness, I can’t say. But “taxation studies” and “a career in sums” as opposed to a career in the actual humanities are clever parodies of Bloom’s influence theory and his career as a commercially successful writer. If this is Bloom, it is a mundane Bloom, and a mediocre one. The real Bloom, it would seem, is hardly present in the book.

What to make of this? I let it simmer for a while, and then I found some hints. First — on his episode of the Our Struggle podcast, Cohen calls Harold Bloom a cross between Larry David and Judge Holden from Cormac McCarthy’s novel Blood Meridian. The Judge is a terrifying character, the leader of a murderous gang of scalpers in the early American West, a seven-foot-tall albino with an occult intensity and an obsessive and powerful intellect. He famously says “Whatever in creation exists without my knowledge exists without my consent.” As a dictum for a literary critic, this is indeed frightening.

And then second, in the back of the book, there is a startling revelation Bloom apparently related to Cohen — that the main character of Philip Roth’s novel Sabbath’s Theatre was based on Bloom, with Roth asking the question “what if Harold, instead of making his parents proud and going to the Ivy League, had gone to seed in the Village in the ‘50s?”. Sabbath’s Theatre is, of course, endlessly shocking, its main character Mickey Sabbath a relentlessly hedonistic, amoral, highly hostile and unsavory and yet somehow irresistible character. I can remember, reading the book years ago, being struck by his otherworldly way of speaking, the way his lines of dialogue emitted a kind of alien light next to the other characters on the page. Something like this light shines out from Bloom’s own writing, and now it seems obvious that aspects of his personality were the basis for the Roth character.8 But also … this very same quality is in Cohen’s book — in Netanyahu himself.

And so, following Cohen’s analogy about Bloom’s personality and the hint from Roth, I asked myself: is Netanyahu meant to be Judge Holden to Ruben Blum’s Larry David? Do these two characters represent Bloom himself, but split apart? If so, then this is deeply troubling, because it would make Netanyahu a partial portrait of Bloom, and in particular he would represent Bloom’s charisma and imaginative power, his genius. Ruben Blum is the mundane Harold Bloom, stripped of any genius; Netanyahu is the genius or daemon, an overwhelming and terribly destructive force.

Is The Netanyahus Harold Bloom’s dream? He would be like the dreamer in Finnegans Wake — psychically divided, longing for his wife, frightened of his waning vitality, reaching back to some authority from the past, some fathering force within himself, and yet always being shoved onward into his own diminishing. Like the “cad”, a morphing menacing figure of the Other that H.C.E. keeps meeting in the Wake, Netanyahu would seem to have some enigmatic connection with the passage of time, the recognition of an ending era, and some hidden guilt in Ruben Blum. He arrives to tell the hero what time it is, and the best the hero has with which to meet him is hesitation, and then withdrawal.

Will our own genius, the spark in each one of us, one day come to announce our doom and collect? Will we too wither as Blum does, in the face of such a threat? Has it already happened?

The deflated feeling as a past era becomes so much junk and empty refuse, ready to be churned back into the great river of time — this is also consonant with the late sections of Finnegans Wake dominated by the “Shaun the Post” figure. Even the vowel bending from “Bloom” to “Blum” is reminiscent of the Wake’s puns. “Shaun” becomes “John” and then “Yawn” and then dissipates. Bloom becomes Blum (a “glum Bloom”, an explainer of Finnegans Wake puns might say) and we are primed for ricorso — for another turn in the cycle of history, for a new era to arrive.

Turn it over again — better to say it’s all Cohen’s dream. He ventriloquizes Bloom with his puppets Blum and Netanyahu. He is the “lord’s last bastard descendant” giving Blum’s in-laws “guided tours for tips” through faded memories of the golden age of Jewish American writing. The “lord” is Harold Bloom, and The Netanyahus is Cohen’s reaction formation against the dominating presence of Bloom himself, of Bloom’s will-to-power over the meaning of Cohen’s work and career.

When Bloom was alive, his friendship and his approval of an author’s work had enormous power in conferring prestige and generating interest. But his personality, reportedly, was overwhelming. He could be immensely demanding, even draining. He saw too much and too clearly, and he wanted too much in return. Both blessing and curse, his endorsement seemed to produce ambivalent responses in the writers themselves.

I’ve tried to gather up the pieces I’ve found over time of Literature in Response to Harold Bloom. A. R. Ammons dedicated his poem “The Arc Inside and Out” to Bloom, and they had a complex relationship.9 David Foster Wallace, at some point, seems to have earned Bloom’s permanent animus.10 I always assumed it was because his odd short sketch “Death is Not The End” from Brief Interviews with Hideous Men must have been about Bloom. If that’s not enough, see page 911 of Infinite Jest, where he quotes The Anxiety of Influence directly, calling it “turgid-sounding shit”. I’ve always thought John Ashbery’s poem “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror”, which plays with the language of criticism, had a reference to Bloom in particular,11 and Bloom himself acknowledges somewhere the playful hints about him in James Merrill’s The Changing Light at Sandover. Not long after Bloom passed away a few years ago, Henri Cole published a poem called “Super Bloom”, and so the cycle continued. And now there is The Netanyahus.

Is Bloom’s influence theory one big metaphor for his own personality? The writer called to struggle with a strong precursor, or even a whole literary tradition, to achieve something original and to earn their fame, may one day also face contamination by Bloom himself, if he happens to like their work and play a role in their career advancement. They must protect themselves from the mark of his approval, if their work is to remain truly theirs.

Cohen is cunning and is up to the challenge. What better way to demonstrate one’s primacy over past literary achievement and over Bloom himself than by writing your way into a dream of his decline? You would re-people his past for him, and remake his psychology. You would choose what to fill and what to empty. You would stand as tour guide for one last look backward at a dying era and let us watch as the daemon returns to reclaim its powers and assimilate them into something new.

You are free to judge my work but be careful, it seems to say to Bloom, because this book is about YOU!

If you liked this essay, consider reading my short follow-up post and my poem in response to the novel.

My title is a phrase from p. 61 of the novel.

p. 51

p. 157, p. 75, p. 113 respectively

p. 114

p. 4

p. 2

p. 4

p. 4 again

Some readers have cast doubt on the truthfulness of these endings sections in the book. See this review in The Guardian and this Twitter thread. Even if the Sabbath’s Theatre detail is not true and is just a falsification from Cohen, the consequences for my interpretation remain the same.

This article goes very far into this fascinating landscape. Says Ammons: “ … Harold wants me to be intense, mad, consistently high. I want to be ordinary, casual, a man of this world …”

Quote from this interview: “ … Bloom says, ‘You know, I don’t want to be offensive. But ‘Infinite Jest’ [regarded by many as Wallace’s masterpiece] is just awful. It seems ridiculous to have to say it. He can’t think, he can’t write. There’s no discernible talent.’ …”

“Self-Portrait in Convex Mirror” link here. I assume the “assholes” here to be mostly literary critics, and Bloom to be foremost in “multiplying stakes and possibilities” and confusing issues “by means of an investing aura” —

“… and those assholes

Who would confuse everything with their mirror games

Which seem to multiply stakes and possibilities or

At least confuse issues by means of an investing

Aura that would corrode the architecture

Of the whole in a haze of suppressed mockery,

Are beside the point. They are out of the game,

Which doesn't exist until they are out of it. …”

Great writing here !