There was a play put on earlier this year called Dimes Square by writer/director Matthew Gasda, in places called “Manhattan” and “Brooklyn”, which are parts of New York, a city I think I must have visited once and even lived in for a few years. I didn’t get to see the play, but I bought a copy of the script and read it, and so I was able to visit the Dimes Square in my mind.

The real Dimes Square corresponds to not quite a geometric shape somewhere in downtown Manhattan, where there is, apparently, a “scene”, which of course does not exist. “Scenes”, like “movements”, are made up to scare people — they emerge spontaneously from a mind in chains set on enchaining others, and so are temples erected for the worship of jealousy and fear. They are the wicked afterthought that appears once the real thing’s already been done. Blake says in one of his raging marginal notes: “Empire follows Art & Not Vice Versa”. A “scene” is the Empire come calling when it hears some art has been made. Somewhere, by someone, a vision was had.

Who had it? Will they have it again? Where did it come from? Will it change us? Will it set us free? Are we a part of it now? Does it have anything to do with my lover, or lovers? Does it have anything to do with “power”? Could I make that power mine? Who could hold it, keep it, who could tell me how?

… We go to the apartment what seems like every night, because the guy who rents it (owns it?) lets us come by — me you and a cell phone’s contact list of disparate parties, most of whom I think I’ve met —

— maybe at a show or a gallery opening or on someone’s roof. Maybe I matched with them on Tinder and even messaged them once, but then they ghosted me and I forgot about it until I saw them in real life and realized who they were. Suddenly we felt there might be something between us after all.

But there’s something between you and me now, isn’t there? This existential suspension we won’t call a relationship … can’t we stay floating here a little longer before it ends? But it hurts. I know you don’t love me …

So says this play’s aching. The group doing the to-the-apartment comings and goings drifts around Stefan, a writer who would seem to have inherited some family wealth who’s published a novel and has just gotten a Netflix deal. He’s the one who’s made his apartment into a scene party spot, who lets the ones of whom he approves gather around him and converge. But it is an ambivalent convergence, as we soon discover jealous sniping flowing freely depending on who’s in the room. Stefan is the one with the apartment, the coke, the alcohol, the creative success, but he’s also, according to Terry,

someone who compulsively seduces people ... charms them ... as a survival strategy ... someone who has dealt with his own sense of inadequacy in all the wrong ways and instinctually activates 'seek and destroy' whenever someone in the same generation demonstrates a greater degree of talent … ... everything this guy does is calculated … 1

So the surface is chill, cute, neurotic, exhausted; but underneath it is lonely, tactical, suspicious. Like good bureaucrats, the apartment-goers “look up and around” — up to their assumed superiors, around to their peers — constantly checking. Sometimes they ask themselves if they really believe everyone else is playing a game too, but they know the answer. It’s like Rosie says: “it’s a bunch of social climbers railing coke at 4 am shitting on their so-called friends”.2

This largely sums up the action of the play — we witness these characters doing mostly that, aimlessly — but some centers can be found amidst the diffuse structure. A very good review in Vulture argues that the play can be read as a battle between Stefan the fake scenester and Terry the real artist. Each represents a kind of hierarchy in which those around them take part: Stefan one of cynical social climbing and artistic careerism, Terry an alternative of authentic transcendence through the power of art. I thought this was convincing at first, but the trouble is if you’re not a Stefan and so feel you must be a Terry, you have as baggage a stubborn pain over an ex-girlfriend, Julia, who cheated on you with Stefan, as well as a certain self-absorption that frustrates your new lover and film collaborator Bora, who complains you never ask her how she’s doing, and who — ah, ok, she also slept with Stefan a while back too. Then, getting worse, at some point during the night Stefan and Bora are on the roof together alone, and you, Terry, are appalled but also … aroused when you find that the creep is actually fucking her on the roof, and so you drunkenly attempt to simultaneously make a move on Stefan’s new not-girlfriend Ashley, which doesn’t really work out.

Terry insists to Bora early in the play that he needs Stefan’s social clout and privileged access in order to advance his film career, but obviously the attachment is more personal than that, and maybe even homoerotic. Near the end of the play, when he cryptically says to Stefan, “I’m going to win, just so you know”, is this the utterance of a heroic defender of real art, or of someone captive to a corrosive obsession? Should we honor Terry, or pity him? Does the play belong to both of them, or is it really all Stefan’s?

Dimes Square has a way of inviting you to pick the character you’re most like, and this dilemma of how to judge each of them emerges for any choice of avatar. Musician Nate is well-established creatively, but it hasn’t seemed to have made him any less anxious or depressed. He loves poet Iris openly, like a “teenager”, he says, but she bluntly tells him she will be moving on soon. “Journo dude” Klay at least has the virtue of being more open and apparently kind than the rest of the crew, but mostly this just seems to have put him on a lower step of the social status ladder. He quickly gets rejected by “scene girl” Rosie when he tries to make a move on her, and he’s pushed around by Dave, an older novelist who comes in halfway through the play. We cling to Dave when he arrives because he rants while Stefan is away, putting him in his place, and yet no one can seem to agree whether Dave’s novel, maybe a classic, is really any good, and — they whisper — whatever happened to that second novel of his? And then there’s editor Chris, who tags along with Dave. Being closer to middle age he has some clarity about himself, but he mostly just tells bad anecdotes (or, rather, the one bad anecdote) and creeps on the women.

Does Chris want to go to Rosie’s pop-up show because she’s a talented painter, or just because she’s cute? Will Nate ever date anyone who isn’t already a fan of his music? Is Ashley innocent, simply along for the ride with Stefan, or is she another knowing social climber? Does she see her future in jaded “scene girls” like Rosie and Olivia? Does Klay see his own future in Dave? Does anyone except for Dave listen to the poem Iris recites near the end? Does Terry respect Bora, or is he just using her? Did we just hang out or was that professional networking? No one is spared.

Maybe Klay is still your best bet for a reasonable center, but then we find ourselves asking why Dave hazes him so much. Is it because Dave believes Klay’s fiction has some potential, that he reminds Dave of himself, or is it just that he’s easy to pick on? We the audience may be just as vicious as the scenesters. I’ll pick Klay, you say, but see how quickly you renege if you find out his writing sucks.

Still, my own hopes lie with him, because at least he maintains his self-respect in the face of insult and rejection. Maybe when he goes home and steps away from the scene he says to himself something like Hal’s soliloquy from Shakespeare’s Henry IV:

I know you all, and will awhile uphold The unyoked humour of your idleness: Yet herein will I imitate the sun, Who doth permit the base contagious clouds To smother up his beauty from the world, That, when he please again to be himself, Being wanted, he may be more wonder'd at, By breaking through the foul and ugly mists Of vapours that did seem to strangle him.

Klay won’t be usurping any English thrones any time soon, but we can hope at least that he has something like this sense of self-direction when he’s alone!

Stefan apparently has been on a “book buying binge” as of late, but the only author mentioned in the stage directions is Foucault. So that all-purpose subversive who gave us ideas like the Gaze and the Discourse, who taught us that “power makes knowledge”, has also given us Stefan.

Stefan would seem to have learned from his reading how to manage the relationships around him, how to get and keep what he wants. He knows himself, and he handles others confidently, exercising his power over them without guilt, without second-guessing. He alone is free from stress and anxiety. Guilty and frustrated after having succumbed to Stefan’s advances on the roof, Bora rages at him after their tryst, and he’s as cold as Iago in asserting his privileges of manipulation and control:

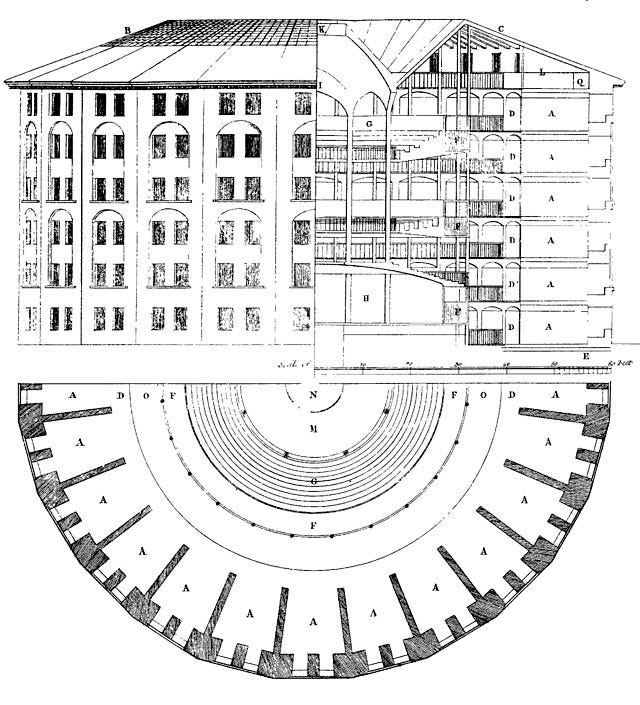

Maybe we can’t blame Foucault for everything, but I thought the detail in the stage directions was too sly to ignore. I took it as the play’s insistence that we have trapped ourselves in these ideas, and are living out the consequences. Stefan has learned to read everything in life as a power game, so to him that’s all there is. It certainly seems to have allowed him to relax, but meanwhile the rest of the characters carry out their purgatorial sentences in the panopticon. And so here we are again — recognizing that, even though there are important lessons to derive from such reading, not everything is Power.

If the Dimes Square denizens had other, better reading lying around, they might learn their place in other hierarchies, other systems of value. We mentioned earlier the alternative of Art and its possibilities of transcendence. Everyone in the play is some kind of creative person, but mostly it seems to make these characters anxious. It serves them best as a subject of gossip, and its power, of a different kind than Stefan’s, remains an almost threatening mystery. The pursuit of art is reduced to a hindrance, a taunt, and gives them no peace.

I was reading Henry James’s novel The Ambassadors recently, which is about an overworked businessman who comes to Europe on a mission to save the son of his wife-to-be from a life as a degenerate Bohemian. He is meant to bring the young man back to America for a respectable career, but he finds himself taken in by the Paris layabouts living the art life, and it gives him new perspective. When I started to read Dimes Square, I imagined myself arriving from my own life of obligation in “Woollett, Massachusetts”, ready to be refreshed, but these Bohemians had me running fast the other way!

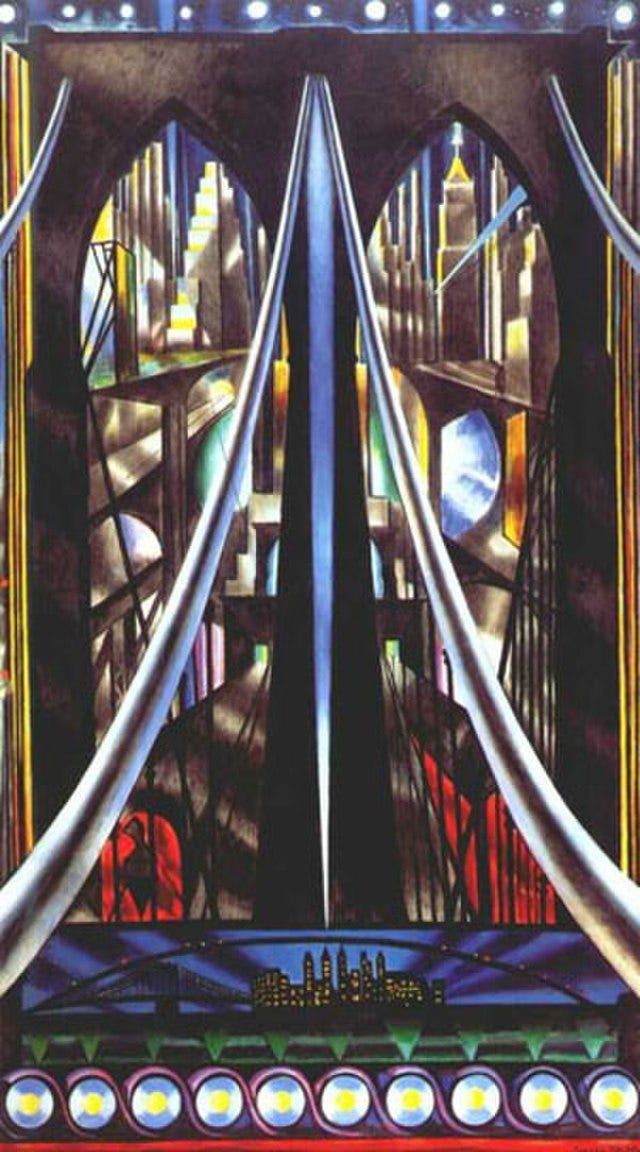

I learned from the poet Hart Crane to be in awe of New York and the possibilities it represents. He saw the city as a great spiritual threshold, bridging future and past, ideal and reality, lover and loved. He joined transcendent Eros to transcendent art in an expansive vision of possible recognition and change. He meant his poems in White Buildings and The Bridge to be rebuttals to the triumph of death he found in T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. He had other hopes for our new technological world.

A younger me would have carried these hopes with him into Dimes Square and stayed, and then met his doom. I would have fallen for all the scenesters’ cynical cons and, more than that, I would have loved them. I would have believed in them. Now I know better.

… You so wholly strange and new and all your own — anatomy and soul and the forces that move them … I see you and feel my own anatomy dissolve — I seem now to be all force, all cause and focus dancing. You are the city’s spaces bending into a new time’s vaulted pace. This cupidinous skein, this avid intimate stage — it is you. Your mouth is a threshold — I am made new.

So says no one in this play, so says not one cursed metropolitan sleaze stealing their way home at night through the city streets. It’s now a hundred years since The Waste Land, and Hart Crane’s challenge to Eliot and to all of us remains unanswered. His art, his Eros, his power are the ones we should be studying. Properly tutored, we would rise from these dregs and renew.

But for now we just have this standing still. Beyond the brutal game of access and privilege and careerism, beyond even the more difficult bureaucracy of creative genius — its delays, its mysteries, its precarity, its tendency to abandon — each character is trapped in a troubled stasis of themselves. They seem to be sending messages continually upward through their own solitary spiritual gates, asking to be let in across the threshold, with no answer forthcoming.

Instead of The Bridge, we find ourselves in a place more like the early John Ashbery poem called “The Grapevine”, too intricate to quote here in full. The poem, though typically obscure for Ashbery, seems to be gesturing at the network of relationships in a group of friends, or maybe a “scene”, or even the audience in a theatre, after the lights come back on after a performance.

The play is a ritual of knowledge and change, and the audience members become something new after it’s over. They sense it as they get up from their seats, but it’s not a knowledge they can keep for themselves — they couldn’t hold it still, they couldn’t write it down. The most they know is that the play took them in — they were a part of it, and it changed them in stealth. Now they regard each other like figures in a game of espionage, asking, “Were they changed too? How will I know? Will they leave me now? Is it over?”. I hear something like this in the poem’s final haunted question:

Whom must we get to know To die, so you live and we know?

It seems to be asking something like: how can I pass through my own private spiritual gates on to something higher without losing you? Would you sacrifice me, if it brought you the changes you knew you needed? Is the “grapevine” a network of love, or jealousy?

Does a scene need lovers, heroes, sacrifices? The stasis of Dimes Square seems to be waiting for something it could kill. It says: “Now I know you all, and you will live in my art as these images, and in watching them together we will come to die so that we will all know anew.” If you’re still following along, take this one step further and say that every character in the play wants to say this to every other one, and you may see something like the darkness and beauty that Ashbery is pointing at.

Why write a play like Dimes Square? Consider it an inoculation against the grapevine, a faithful record of a scene’s shifting bids at knowledge and capture. Whether person or image, the lesson is the same: unless you learn to stand aside it will take you.

p. 35

p. 52

Just completely beautiful writing. I was taken in from the first few paragraphs.

Great review!