Ignorant of Gravestones

REVIEW: War and peace and presence in Tim O'Brien's Dad's Maybe Book

I saw Tim O’Brien in 2007, when I was seventeen and he came to give a talk at my college. He must have talked about being a writer or being young or being a student, but I only remember the letter he shared at the end, addressed to his son, who was sixteen months old. He said that he had written this little thing to tell his son how much he loved him, and that maybe it would turn into a book one day.

Sometime last year a stray thought led me to check O’Brien’s Wikipedia page and there it was, Dad’s Maybe Book, published in 2019. His last book before that was in 2002. The book starts with a version of the letter I heard in 2007, and in it O’Brien says that a father’s chief duty is to be present. “And I yearn to be with you forever, always present, even knowing it cannot and will not happen”.1

In another early chapter, O’Brien and his wife learn at a hospital visit that their infant son Timmy has severe acid reflux, and a simple dose of Prilosec puts their house at peace after weeks of non-stop crying. Marveling at the new quiet, O’Brien finds a part of himself missing the ordeal:

… I’m also feeling a kind of nostalgia, the sort of backward-looking tongue-probing surprise one feels after an aching tooth has been pulled. I don’t miss all the horror, of course. But I do miss surviving the horror … This sensation, whatever it is, reminds me a bit of what I’d once experienced in Vietnam after a firefight ended, when something that was so excruciatingly present became so shockingly absent.

I had been afraid my son would die.

I am still afraid. I will always be afraid.2

On Christmas Eve he is present with his family and yet is still there on a “sad and fearsome Christmas Eve in Quang Ngai Province”. 3

He is an old father, approaching sixty with two sons under ten, and he knows his decline, maybe even his death, is coming soon. He fears he will be cut off from the years they might come to know him more deeply, as adults, and so the book is meant as a preservation of his voice for the future, a ghost of their father for when the boys become men.

There is so much to tell them, and he lets his “maybe book” roam. He writes about Hemingway, his own father, magic tricks, memories, jokes, truth and fiction, growing old, the war, the war, the war. He warns of the dangers of absolutist thinking, of too much love of certainty and the seduction of easy answers — even as he watches himself become more complacent and susceptible to zealotry, more potentially hypocritical.

In the middle of the book he returns to his Minnesota hometown for the first time in a long time, and an old familiar fury rises up:

For decades, I had borne a knotty, cancerous grudge against this place. I still did. The citizens of Worthington, Minnesota, had sent me to war, and I took it personally, and I took it personally because it was personal. Back then, in August of 1968, there was not yet a national draft lottery. Luck was not yet an issue. Mathematics did not yet govern. In those grim days just prior to the Democratic convention in Chicago, hometown draft boards did the dirty work. One father chose another father’s son to go off to the other side of our planet and kill people and maybe die. Or it was that housewife and no other housewife — a housewife with a name, maybe Helen, maybe Dorothy — who circled the name of another housewife’s fresh-faced little boy — or a man who had very recently been a little boy — and then, after the circling was done, it was that living, breathing circler of names who scurried off to Wednesday-night bingo or Friday-night church suppers or Saturday-night square dancing. How monstrous, I’d once thought. How monstrous, I still thought. Circle the name of your own darling son. Circle the name of your precious daughter and your husband and the guy in the cowboy hat calling your Saturday-night square dances. And if you’re so hot for war, what the fuck are you doing in Worthington, Minnesota? What the fuck are you doing choosing other people’s kids to fight a war you’re unwilling to go fight yourself? I used to yell these things, and many similar things, as I drove around Lake Okabena with a yellow draft notice in my billfold …4

He says: “This fury may eventually go away. I hope not.”

In a chapter called “Outrage”, he offers bullet points to his sons for future instruction, each angrier than the last. Number 26: “Three million dead people, and how many of us think about Vietnam at all?”5 His hope for his sons is “a life of outrage”, of “ferocious caring”.

All this amidst just being a dad, the humble fumbling with day-to-day living in peace. Helping with homework, fighting about screen time, planning fatherly history lessons and reading assignments, just caring for his kids. The only way to do this properly is to stay present, achingly in love. He must be honest, he must keep his guard down, he must stay himself. Life is simple, simple.

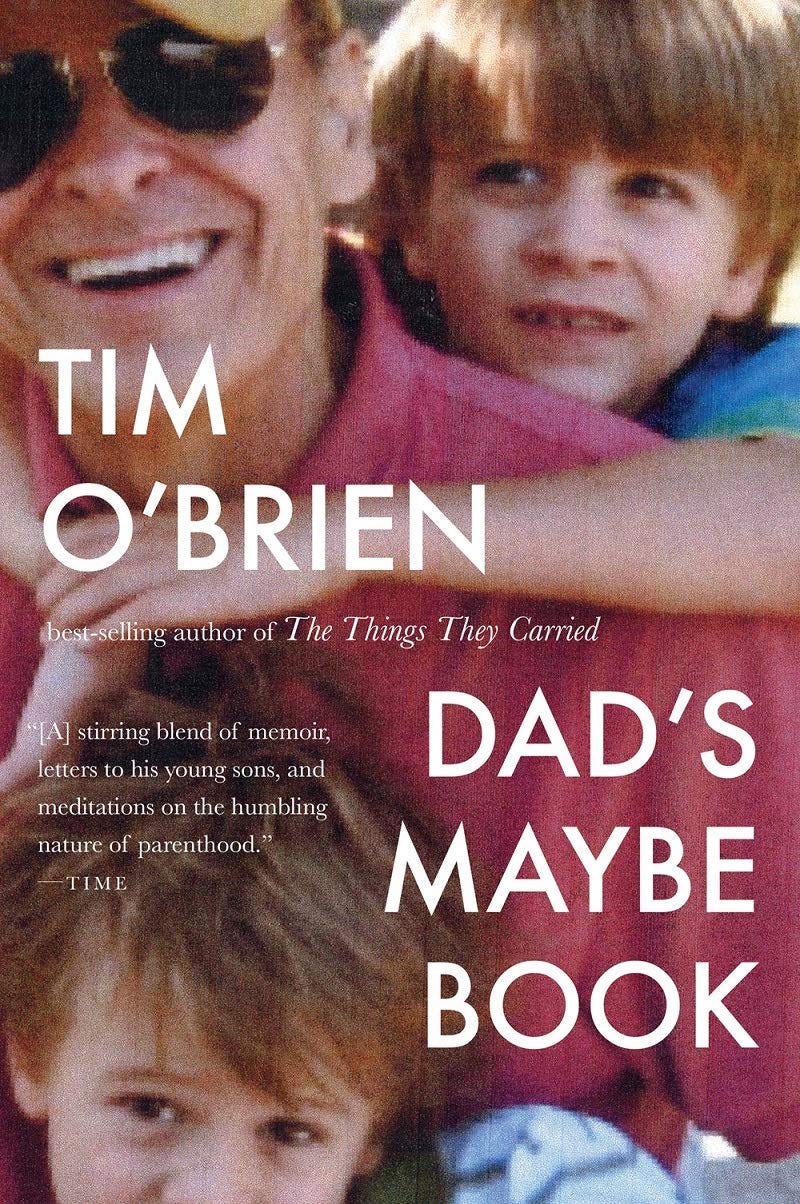

There are some photos of his sons included in the book. They are bright miracles; they have the beautiful open faces of children. They are enormous in an instant and suddenly fifteen years old. At every stage, O’Brien and his wife have the look of people who cannot believe their luck.

Will it really be possible to keep the right sense of things burning? Is that all that’s needed, forever, just practicing being here, right now? Absurd, absurd! We are drunk, distracted, deluded, unreal. Every day and every pathetic second we need to be reminded of reality, and we can’t even stand having it called “reality” for too long, and need to call it some new word just to feel alive again, and soon enough we get tired of that one too. Oblique reaching for an oblique object on ground that’s slipping away.

I read O’Brien’s book and I was shamed again into presence, arrested again into self-consciousness, propelled into fierce hatred and contempt. I felt I could hold onto old pain, and I felt it keep me alive, and then loving overwhelmed my senses.

If you liked this essay, consider reading my follow-up post reviewing the documentary The War and Peace of Tim O’Brien.

My title is a phrase from p. 3 of the book.

p. 3

p. 21

p. 38

p.169

p.196