Last year I read Shakespeare’s play Cymbeline for the first time, and then two tried two adaptations — the 2014 feature film starring Dakota Johnson, and the BBC version with Helen Mirren from 1982.1 The Dakota Johnson film was so bad I had to turn it off, but the BBC version was much better, though still uneven.

It’s interesting to note how much different Shakespeare plays are available to us. Macbeth, for example, seems to me in our time to be well-understood. We know how to play it, direct it, put it on film. Maybe because of its short length, or the small cast, the narrow focus of the action, it’s hard to mess this one up. Even when parts are uneven, the play’s themes come through.

There are easy plays and easy roles. I’ve seen A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Much Ado About Nothing performed many times, without much trouble. These are relatively benevolent, fun to play, easy to understand, not opaque or problematic, have equal parts for men and women, with no oversized roles.

When the roles get bigger, there are characters with popular recognition and widespread understanding, whose personalities come through even when directors experiment. I think the well-known characters from Romeo and Juliet are like this, for example. Even in an experimental treatment of the play like the movie with Leonardo DiCaprio, the characters are still familiar to us.

We know King Lear, but he is very hard to play. We know Falstaff, but most of us don’t love laughter enough anymore to play him. I’ve made the case in the past that we don’t play Hamlet well and have inherited an overly solemn and unthinking approach to his play. We are weighed down by the play’s history on film, and by our overfamiliarity with its famous scenes.

Of Shakespeare’s late romances, The Tempest is always popular, and I’ve seen A Winter’s Tale performed a surprising number of times, but I have never seen Pericles or Cymbeline performed onstage.

Judging by the movie versions, Cymbeline is not wholly available to us, but it is a play with a troubled history of interpretation. You go through the commentaries and find the critics at turns frustrated, perplexed, enamored, apologetic. They say many of the same things, and then about a few things they disagree, but most of them come away confused. The films I watched seem confused too.

What would a well-played version of Cymbeline look like? This is my humble attempt to offer some ideas.

Imogen’s Virtue

The first thing to fix about the films is Imogen. She is the central character in the play, and her personality is the play’s ultimate subject.

It is odd that Imogen is not more famous in our time, because she has long been considered one of Shakespeare’s greatest characters, even by commentators who dislike the play. The critic Harold Bloom, who strongly dislikes the play and has some of the milder praise of Imogen, says it is impossible not to love her.2 The superlatives ascend from there. The critic William Hazlitt says: “Of all Shakespeare’s women she is perhaps the most tender and the most artless.”3 The Victorian writer Anna Jameson says she “… unites the greatest number of those qualities which we imagine to constitute excellence in woman,” and calls her an “angel of light.”4 The poet Algernon Charles Swinburne sees Imogen as the crown of Shakespeare’s vision, and ends his book on Shakespeare in rapture —

The very crown and flower of all her father’s daughters,—I do not speak here of her human father, but her divine—the woman above all Shakespeare’s women is Imogen. As in Cleopatra we found the incarnate sex, the woman everlasting, so in Imogen we find half glorified already the immortal godhead of womanhood.5

I like some of the more down-to-earth appreciations of Imogen. Jameson has some nice remarks about her —

In her we have all the fervour of youthful tenderness, all the romance of youthful fancy, all the enchantment of ideal grace,—the bloom of beauty, the brightness of intellect, and the dignity of rank, taking a peculiar hue from the conjugal character which is shed over all, like a consecration and a holy charm.6

— though sometimes she makes Imogen sound more delicate than she is. There is some well-done close reading by an author named George Fletcher7 that, like Jameson, emphasizes specific details of her outward virtues — her fine features, her graceful manners, her melodious voice. This is a woman who renders Iachimo awestruck, who drives the rejected Cloten to infuriated despair, and who is openly loved and admired by the other characters in the play.

But all this is absent from both film versions. At best Imogen is seen as something like another Juliet, but there is a dour aspect to her character in both films. The directors and actors seem to think that Imogen’s story is predominantly one of pain, and that the performance should reflect this. But this is far from what we find in the commentaries on the play.

Imogen’s superior outward qualities must be emphasized, but this barely gets us started. Fletcher is right to say these outward qualities should be understood as being in harmony with her soul —

Her personal beauty is of a character which so speaks the beauties of her soul,—her mental loveliness so perfectly harmonizes with her outward graces,—that it is difficult, nay impossible, to separate them in our contemplation. In this case, most transcendently, do we find the spirit moulding the body, the sentiment shaping the manner, after its own image, even to the most delicate touches. This meets our apprehension at once, even if we look upon her with the eyes of Iachimo, the unsentimental though very tasteful eyes of the elegant voluptary and accomplished connoisseur. It was not her external charms alone, however peerless, that could daunt a man like him; it was the heavenly spirit beaming through them at every point.8

The German critic Georg Gottfried Gervinus has some of the best appreciations of Imogen —

The characteristic feature of this nature, which displays itself again and again in all the strange and most various situations in which the poet has placed Imogen, is her mental freshness and healthiness. In the untroubled clearness of her mind, and unspotted purity of her being, every outward circumstance is reflected, unruffled and undistorted, in the mirror of Imogen’s soul, and at every occasion she acts from the purest instinct of a nature as sensible as it is practical. Rich in feeling, she is never morbidly sentimental; rich in fancy, she is never fantastic; full of true, painful, earnest love, she is never touched by sickly passion. She is mistress of her soul under the most violent emotions, self-command accompanies her strongest feelings, and the most discreet actions follow her outbursts of vehement passion, even when bold resolutions are required.9

…

In this guileless nature evil impressions are not lasting, and she does not torment herself with too much reflection; she is led by the most enviable instinct ... Naturally cheerful, joyous, ingenuous, born to fortune, trained to endurance, she has nothing of that agitated passionateness which foretells a tragic lot, and which brings trouble upon itself of its own creating. At the end of the play, when, shaking off her long sufferings and cruel deceptions, she gives herself at once to the happiest feelings ... we feel that this being, fit for every situation, improved by every trial, has been wonderfully gifted by nature to be equal to every occasion.10

When asked to name great parts for women in Shakespeare, we might say Cleopatra, Lady Macbeth, Gertrude, Juliet, Portia from The Merchant of Venice, Viola from Twelfth Night, Beatrice from The Taming of the Shrew, Rosalind from As You Like It, Cordelia from King Lear, and so on.

Hers would be a difficult part to play, but Imogen deserves to be included in this list. These appreciations of her should begin to apprise us of how to see her differently.

Rethinking Iachimo

Iachimo, the Italian rogue who wagers he can seduce Imogen, has been unfairly minimized by most commentators. He is actually one of the more intelligent characters in the play, possibly even the play’s most intelligent character, and has not been well understood.

The scene in which he attempts to seduce Imogen merits closer reading. In this scene, he arrives in court and presents himself, and he offers Imogen a fake letter from Posthumus and listens to her read it aloud.

Then he recites this strange and elaborate speech, which seems to come out of him half-involuntarily —

IACHIMO

Thanks, fairest lady. What, are men mad? Hath nature given them eyes To see this vaulted arch, and the rich crop Of sea and land, which can distinguish ‘twixt The fiery orbs above and the twinn’d stones Upon the number’d beach? and can we not Partition make with spectacles so precious ‘Twixt fair and foul?

IMOGEN

What makes your admiration?

IACHIMO

It cannot be i’ the eye, for apes and monkeys ‘Twixt two such shes would chatter this way and Contemn with mows the other; nor i’ the judgment, For idiots in this case of favour would Be wisely definite; nor i’ the appetite; Sluttery to such neat excellence opposed Should make desire vomit emptiness, Not so allured to feed.

IMOGEN

What is the matter, trow?

IACHIMO

The cloyed will — That satiate yet unsatisfied desire, that tub Both fill’d and running, ravening first the lamb Longs after for the garbage.

This is an arresting moment, though it takes time to puzzle through it. It’s puzzling in part because it’s characteristic of the romances’ opaque style, and here the rhetoric gets so opaque that Imogen herself does not understand what Iachimo is saying.11

Upon encountering her, he has become abstracted. Unlike the commentators I’ve read, I read his strange philosophical meditation as sincere, but more on that in a moment. First, what does it mean? He says that mens’ eyes can distinguish between fair and foul, and asks somewhat philosophically what is it exactly that allows them to know the difference. “Fair” here means more than just outwardly beautiful. Imogen’s surpassing virtue, inner and outer, becomes clear to him all at once, and overwhelms him.

He offers a series of negative answers to his own question. It can’t be in the eye, this faculty that apprises men of her surpassing virtue, because apes and monkeys have eyes and would, if I’m reading his phrasing correctly, choose a whore and throw out the virtuous woman. It can’t be in the judgment, because idiots, who lack judgment, would still choose her. And it can’t be in the appetite, because something strange happens to the whoring man when he puts “sluttery” next to “such neat excellence.” He finds that though his stomach is empty that he’s not hungry, and even that he’s repulsed enough to “vomit emptiness.” (Dr. Johnson reads this as disgusted dry heaving at the sight of “sluttery” next to Imogen). Looking on “sluttery,” he loses his appetite — that is, it cannot be in the appetite, as to choose such neat excellence would be due to his appetite having been lost.

Where then, does such a faculty lie? Then he stops, struck: “The cloyed will.” This does not quite fit the more general philosophical way he first asked the question. It’s as though Iachimo has suddenly turned to himself, shocked into self-recognition. Speaking for himself, he theorizes that he can apprehend Imogen’s rarity only because he has toured through all the “garbage” in whorehouses across Italy, and so has, in his strange metaphor, overfilled the tub of his will, even as the faucet keeps running.

He started this journey by first, as he says, ravening a lamb, and it is as though in meeting Imogen he has met that lamb again, but now in his condition of a “cloyed will.” Is he thinking of the first woman he ever seduced, presumably a virgin? Now he sees that virgin anew.

And how strange, to make his career as a seducer a matter of “will.” This is the edge of some deeper insight about himself, and signals a possible change that he might undergo, if only he would allow it. This change has been “charmed” out of him all at once, but he holds it off.

He recovers himself a little and gives his false account of Posthumus in Italy. This is supposed to be the shocking tale of Posthumus the rake, mocking and sleeping around, but again Iachimo involuntarily lapses into brooding over himself —

IACHIMO

Ay, madam, with his eyes in flood with laughter: It is a recreation to be by And hear him mock the Frenchman. But, heavens know, Some men are much to blame.

IMOGEN

Not he, I hope.

IACHIMO

Not he: but yet heaven’s bounty towards him might Be used more thankfully. In himself, ‘tis much; In you, which I account his beyond all talents, Whilst I am bound to wonder, I am bound To pity too.

IMOGEN

What do you pity, sir?

IACHIMO

Two creatures heartily.

“Heaven’s bounty towards him might be used more thankfully.” “Some men are much to blame.” His story is unwittingly a description of himself, and I think when he says he pities “two creatures,” he is partly thinking of himself and his attempt to seduce Imogen, or may even be turning his thinking again to the first woman he seduced. Now he pities her, and even pities himself.

What sudden change! He says in another dense passage that the touch of a woman like Imogen would inspire his soul to oaths of loyalty and would release him from his life as it is, full of “plagues of hell,” and he likens himself to a candle being snuffed out.

All the commentators I’ve read gloss over the content of Iachimo’s speeches in this scene, and they wave away his behavior as Italian “virtuosity.”12 The two film versions seem to read it similarly, though the BBC version at least treats the “What are men mad?” portion as a separate aside before Iachimo’s speech begins. But otherwise he is portrayed as always purposely deceptive and maintaining control.

But I think the correct reading is that he has really lost himself upon encountering Imogen, and that he has to keep recovering throughout the scene. These moments of losing himself must be played as sincere. He should be seen to waver, oscillating between cunning control and being authentically dumbfounded, confusing his schemes with involuntary self-revelation. He should flounder — his actions in the scene are hardly a successful approach to seduction — and be baffled by his floundering. His final throwing himself upon Imogen has to be both an attempt at the climax of his performance of feigned outrage over the supposed infidelity of Posthumus and a barely contained outrage at himself.

Once Imogen has denied him, a cooler scheming tendency returns as he shifts to his alternate plan of infiltrating her room, but already it feels tired, just done out of habit. Iachimo has passion and an active intellect in the scene where he sneaks into her room, but I do not read him as so potently sinister here as some critics.13 His scheme in this scene is executed almost by rote.

Other critics, like Bloom, dismiss Iachimo entirely. I think this is closer to the truth, but it is not because of some smallness of character in Iachimo. Instead I think we should understand him as having been diminished, all in one encounter. He reverts to his old ways, but they suddenly have become stale. It is as though the whole history of his life has been made obsolete.

Posthumus as Anti-Hamlet

It’s possible Posthumus is among Shakespeare’s most unlikable creations. Some critics see him as a noble character and attempt to defend his honor. They emphasize the trials he endures, and they read straightforwardly the god Jupiter’s speech near the end of the play, about virtue needing to be tested in order to be proven.

Other critics see him as a mediocrity, unworthy of Imogen. The responses range from amiable dismissal to full-blown outrage. Harold Bloom is the height of this hostility to Posthumus, calling him a “husbandly dolt.”

He is an orphan raised by the king, and so not of royal blood. Unlike Imogen and her lost brothers, we do not have any aristocratic assurance about his character. How then should we estimate him? It is a frustrating puzzle.

I think it is significant — and not remarked upon enough — that this puzzle is one that is openly grappled with by the characters in the play. The two gentlemen who discuss the state of the kingdom in the opening scene start with perplexing rhetoric on this topic. The First Gentleman is telling the Second about Imogen’s marriage, her rejection of Cloten and her choice of Posthumus —

FIRST GENTLEMAN

He that hath miss’d the princess is a thing Too bad for bad report: and he that hath her— I mean, that married her, alack, good man! And therefore banish’d—is a creature such As, to seek through the regions of the earth For one his like, there would be something failing In him that should compare. I do not think So fair an outward and such stuff within Endows a man but he.

SECOND GENTLEMAN

You speak him far.

FIRST GENTLEMAN

I do extend him, sir, within himself, Crush him together rather than unfold His measure duly.

This is a peculiar way to describe a virtuous individual — to say that one is “crushing together” the “stuff within” in order to convey the man’s virtue, as if all the inner substance had to be vacuumed up across vast reaches of space into the ultra-dense “stuff,” which could never properly recommend itself but through “unfolding” its “measure duly” (which is actually what happens in the play).

This question of needing to unfold actually suggests an anxiety about what’s within. Perhaps there is no stuff inside Posthumus at all. There is Posthumus’s appearance, which we are easily confident is “fair,” even, we gather, exceptionally handsome, but already there is much hesitating about the essence within. The characters feel there must be something profound about this man that Imogen has chosen for her husband, and yet they are perplexed.

Even when characters aren’t perplexed by Posthumus, there is irony present. I still find myself puzzled as to how to interpret the Frenchman’s estimation of him, when he says: “I have seen him in France: we had very many there could behold the sun with as firm eyes as he.”

This might be the Frenchman’s joke, but I think he is maybe saying that Posthumus is of estimable courage but nothing special.14 Pisanio is also unwittingly ironic in the scene when he describes Posthumus departing on the boat to Italy and says that his soul was slow but his ship was swift. Posthumus does indeed have a slow, lumbering soul. He has a clumsy wit and a poor imagination, and he shows this throughout the play. His first metaphor in his loving farewell to Imogen is quite bad —

… thither write, my queen, And with mine eyes I’ll drink the words you send, Though ink be made of gall.

He will drink the words of the letter with his … eyes? Even if the ink tastes bitter. Hmm.15 I like the next part, when he says

POSTHUMUS

Should we be taking leave As long a term as yet we have to live, The loathness to depart would grow. Adieu!

His loathness to depart would only possibly be greater if the term of their separation would be for the rest of their lives, and then one word later he abruptly says “Adieu!”. This is his special stupidity on display.

After this Imogen urges him to stay a little longer, and gives him a ring to signify their faithfulness to each other. Posthumus says of the ring —

Remain, remain thou here While sense can keep it on.

This is funny because he will of course very quickly take it off when he agrees to the wager after just one conversation with Iachimo. He is indeed a “senseless” man. Shakespeare makes this clear down to the last scene, when in a final embarrassing moment Posthumus does not recognize Imogen in her disguise as a male servant and throws her roughly to the ground when she rushes to embrace him. Poor Pisanio has an outburst at his master for this, as if he can’t take it anymore.

Harold Bloom among all critics is the most outraged by Posthumus. He complains: “The wonder again is why Shakespeare so consistently labors to make Posthumus so dubious a protagonist, so estranged from the audience that we simply cannot welcome his final reunion with Imogen.”16

Bloom is outraged by Posthumus, and outraged by the whole play. He reads Cymbeline as a work of comprehensive self-parody. Imogen recalls Cordelia from King Lear, as Cymbeline does Lear himself. A scene where Imogen is carried onstage by her brother and she is presumed dead recalls the scene of Lear carrying Cordelia. The Queen in Cymbeline, who Shakespeare doesn’t even bother to name, is like a mediocre Lady Macbeth, and her son Cloten is something like a failed Edmund from King Lear. Their patriotic rhetoric, complete with weird metaphors, parodies speeches from the history plays. Iachimo, whose name some critics take to mean “little Iago,” is like a faded Iago. And so on.

Bloom cannot understand why Shakespeare would so thoroughly travesty his own work, and ends his chapter on Cymbeline with a note of frustrated incomprehension. It surprises me that this critic who has taught us so much about the subtleties of influence (and in the case of Shakespeare, of the mind’s influence on itself) did not take things further in his interpretation of the play. He seems poised on the edge of some larger understanding, but refuses to take the leap.

Start with this assertion then — that Posthumus is meant to be a parody specifically of Hamlet, to be the anti-Hamlet.

I have seen discussion of Posthumus’s name as indicative of his orphaned circumstances, but I have not found any critic who points out that it could be an echo of Hamlet’s “imposthume,” which Bloom discusses in a chapter of his book Hamlet: Poem Unlimited.17

Hamlet uses this word when he runs into the Norwegian army captain who is marching men across Denmark to claim territory in Poland. The captain says the territory is useless, no good for farming and not worth the effort, and Hamlet responds that such a pointless military expedition is symptomatic of a kingdom with too much wealth and nothing better to do —

HAMLET

Two thousand souls and twenty thousand ducats Will not debate the question of this straw: This is the imposthume of much wealth and peace, That inward breaks, and shows no cause without Why the man dies. I humbly thank you, sir.

“Imposthume” means an abscess or cyst, a pus-filled swelling under the skin. Here the infection isn’t drained out but instead breaks inward into the body, killing the host. Hamlet is talking about the corruption of Norway, but he is always multiplying ironies in unexpected ways, and hardly lets an event pass without relating it to his inner life.

Bloom interprets the imposthume as signaling the change of Hamlet’s character in Act V, and as a central metaphor for Hamlet’s consciousness. Bloom also sees this symbol as central to Shakespeare himself. This is the moment when a new mode of dramatic representation begins, in Hamlet and in Shakespeare —

Is The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark Shakespeare’s imposthume? The break into inwardness was unsurpassable, and made possible Iago, Othello, Lear, Edmund, Edgar, Macbeth, Cleopatra, Antony, an eightfold whose paths to the abyss were chartered by Hamlet, death’s ambassador to us. G. Wilson Knight first called Hamlet the embassy of death, and once remarked to me that he himself could confront the play only because of his strong belief in immortality. We do not know what Shakespeare believed about the soul’s survival. Before Act V, Hamlet is confident of his soul’s immortality, but I think he is different after his return from the sea, and I suspect he courts annihilation. When the impostume breaks, the man dies, and perhaps the soul with him, for in Hamlet consciousness and the soul have become one.18

More than “inwardness” or “consciousness,” I like better Bloom’s related term “self-overhearing,” which describes when a person listens to themselves as though they are observing a dramatic character. The right kind of listening induces a self-awareness that can change their relationship to themselves. “Inwardness” is the place to which they return, like a theatre in their mind, to reconceive of their relationship to themselves. Hamlet takes this practice of self-overhearing further than possibly any other character.

But Posthumus is incapable of inwardness. This is the great joke of his character, and why he is so frustrating. The whole elaborate machinery of the play’s plot does nothing to prove his supposed virtue, and only proves that he is wholly senseless to the self-consciousness that would allow him to break inward. He can speak a soliloquy and never pass into self-overhearing, and no catastrophe of any magnitude can induce him to change his relationship to himself.

He is a kind of freak Stoic, incapable of internalizing anything. Neither virtue nor corruption manage to penetrate him. He knows only outward action and its fruits. He knows others acting on him, and himself acting on others.

When he contrives his strange penance for the crime of having ordered Imogen killed, which is to don a peasant’s rags and fight on the side of England in the war near the end of the play, he makes a clumsy statement that ends: “I will begin/ The fashion, less without and more within.” He’s repeating the same framing from the Gentlemen’s conversation from the first scene, and this is the joke — that there is nothing within. Underneath his peasant’s rags is his warrior’s body, and this is all he means.

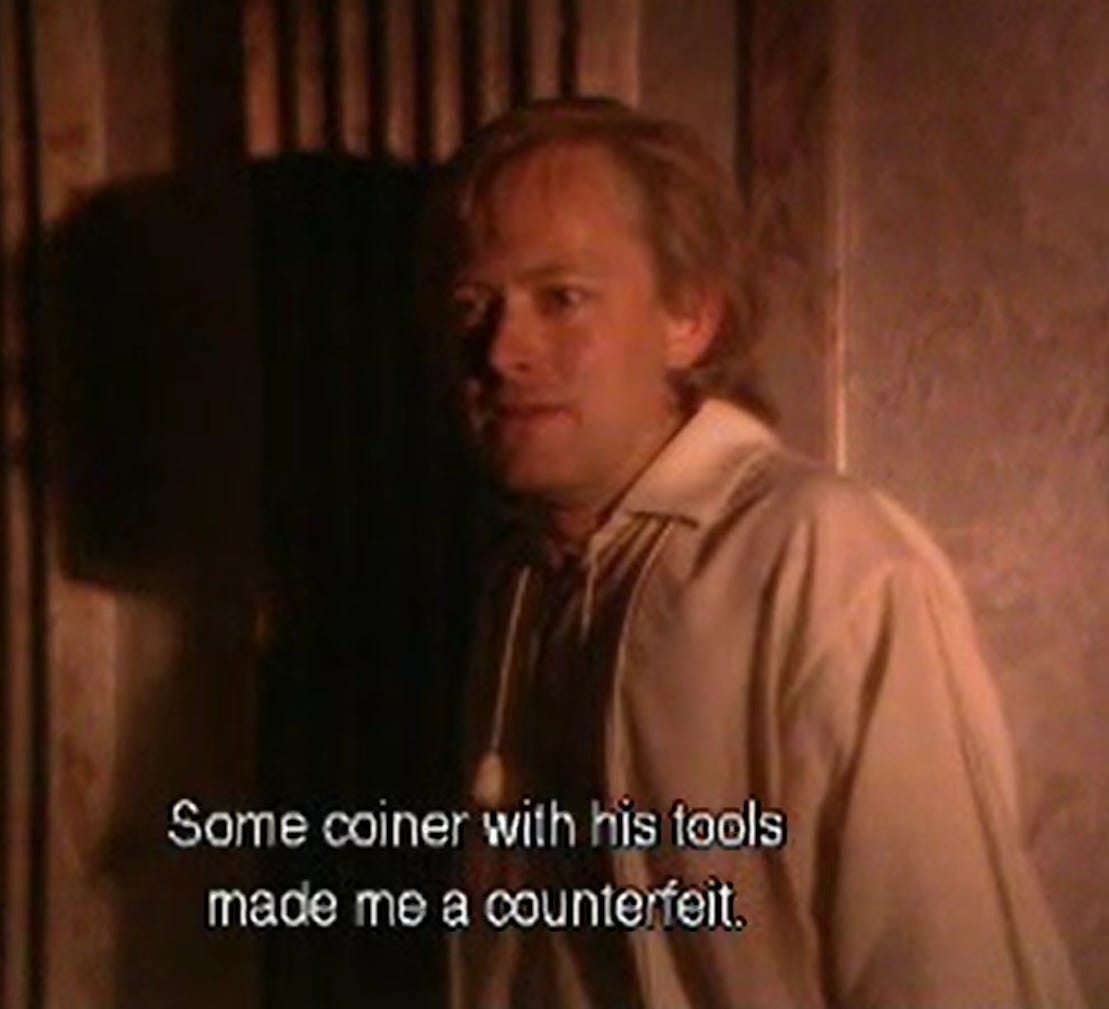

Later on, after Posthumus is jailed by the English army and ordered to be hanged, he speaks with the Gaolers who will serve as his hangmen. The First Gaoler chides Posthumus for being so eager to die, and for being so seemingly confident in his sense of what will happen after death. In a crazy parody of Hamlet’s “To be or not to be” speech, when Hamlet longs for a sleep that would “end the heartache and the thousand natural shocks that flesh is heir to,” the First Gaoler says:

FIRST GAOLER

Indeed, sir, he that sleeps feels not the tooth-ache: but a man that were to sleep your sleep, and a hangman to help him to bed, I think he would change places with his officer; for, look you, sir, you know not which way you shall go.

Posthumus would indeed be free of toothaches after death, but not free of what dreams may come, which, if his present state is any indication, will not be pleasant.

Posthumus believes he is going to face annihilation, that his soul will be destroyed after he passes beyond the threshold of death, but the First Gaoler says that he should not be so confident of this. Again echoing Hamlet and his “from whose bourne no traveler returns,” he says: “I think you’ll never return to tell one.”

It is interesting to go back to Bloom’s explanation of Hamlet and the imposthume. I am not sure if I agree with Bloom’s assertion that after Act V Hamlet no longer believes in the soul’s immortality. Some more detailed analysis may have to be worked out.

But the First Gaoler certainly does not agree with this, or at least he feels that a man should not be so eager to die, and he marvels at Posthumus’s more-than-Roman Stoicism —

FIRST GAOLER

Unless a man would marry a gallows and beget young gibbets, I never saw one so prone. Yet, on my conscience, there are verier knaves desire to live, for all he be a Roman: and there be some of them too that die against their wills; so should I, if I were one. I would we were all of one mind, and one mind good; O, there were desolation of gaolers and gallowses! I speak against my present profit, but my wish hath a preferment in ‘t.

“I would we were all of one mind, and one mind good” — is this Shakespeare admitting defeat? It is as though he has been met with the ultimate example that would resist his universalizing.

When Posthumus wakes up from his dream in Act V and reads the prophecy of his fortune in the book left by the god Jupiter, he says:

‘Tis still a dream, or else such stuff as madmen Tongue and brain not; either both or nothing; Or senseless speaking or a speaking such As sense cannot untie. Be what it is, The action of my life is like it, which I’ll keep, if but for sympathy.

The dream and the prophecy are as senseless as his life. Bloom complains about this at the end of his frustrated chapter on Cymbeline:

Through Posthumus, I hear Shakespeare observing that the action of our lives is lived for us [that is, for ourselves alone], and that the desperate best we can do is to accept (”keep”) what happens as if we performed it, if but for ironic sympathy with ourselves. It is another of those uncanny recognitions in which Shakespeare is already beyond Nietzsche.19

I would respond that this is arguably one of the things that outrages Hamlet most, and is one starting point for his speculations.

But the teachings of Hamlet would mean nothing to Posthumus — his sterling senselessness has proved impenetrable. Only an audience trained in the kind of seeing taught by the previous plays could recognize this for what it is. But such an audience has been silenced and forced to repent, as Iachimo is in the end.

Imogen’s Will

Some critics praise Imogen in general terms, saying she represents a female ideal, but I haven’t found much analysis or appreciation of her specific personality, which would be more useful. Something about this play’s tendency to baffle readers seems to encourage them to assume she has less depth than she does. I think it is also the play’s tendency to recapitulate Shakespeare’s earlier work that makes it more difficult to see Imogen clearly. Commentators tend to explain Cymbeline in terms of the earlier plays. Jameson says —

Imogen, like Juliet, conveys to our mind the impression of extreme simplicity in the midst of the most wonderful complexity. To conceive her aright, we must take some peculiar tint from many characters, and so mingle them, that, like the combination of hues in a sunbeam, the effect shall be as one to the eye. We must imagine something of the romantic enthusiasm of Juliet, of the truth and constancy of Helen, of the dignified purity of Isabel, of the tender sweetness of Viola, of the self-possession and intellect of Portia ... 20

The critic Harold Goddard has a similar explanation —

Simplicity is the most complex thing in the world, and many rereadings of the role are necessary in order to appreciate the subtlety with which Imogen is characterized. Like Hamlet, she is an epitome, uniting in herself the virtues of at least three of Shakespeare’s feminine types: the naive girl (in boy’s costume part of the time), the queenly woman, and the tragic victim. It is as if the poet had consciously set out to endow his heroine with the finest traits of a dozen of her predecessors.”21

That she has both such variety and simplicity makes things difficult. In the above quote, Goddard also mentions Hamlet because he has just quoted a remarkable statement by Gervinus —

Imogen is, next to Hamlet, the most fully drawn character in Shakespeare’s poetry; the traits of her nature are almost inexhaustible ... 22

At first this seems almost insane, but I think we may need to come around to its truth in order to read Imogen correctly.

One key to understanding her is her virginity. There is some disagreement about this among commentators,23 but I think the play does not make sense if Imogen and Posthumus have already consummated their love. She protects her “treasure,” as she puts it, from the “siege” of Cloten, Iachimo, and also of Posthumus himself.

This last part is suggested in the dialogue, as when Posthumus complains she “oft” refused him.24 We know Posthumus is exceptionally handsome and that he has spent some time in profligate Italy, so he would seem to have had sexual experience and to be used to getting his way. He is also a man of action, as we’ve said, and I think it is Imogen’s refusal of his sexual advances that make him see her differently. This explains his remark at Philario’s house when he says he had a previous dispute about defending Imogen’s honor that he now realizes was “not altogether slight.” Between these two incidents, I surmise that he has attempted to bring Imogen to bed and has been refused. It would seem this is the first time this has happened to the handsome Posthumus. (How absurd, that his exchange with Iachimo is not the first time he’s had a fight about his woman’s honor. Note too that Iachimo, a man of penetrating intelligence, understands Imogen right away upon meeting her, but Posthumus needs to act before he can form his judgment.)

I found a few useful essays on Imogen’s virginity, which is not much discussed in the more general commentaries. The critic Karen Bamford discusses the political significance of Imogen’s virginity.25 Before she discovers her orphaned brothers, any child Imogen would have with Posthumus would be heir to the throne. This is perhaps part of her motivation in withholding from him.

Other commentators go further, and claim to find repressed perversity in both Imogen and Posthumus. The poet Geoffrey Hill writes of her supposed “naivete that wants to be devoured.”26 Hill seems to suggest there is something sado-masochistic in their relationship, as though they get mutual perverse pleasure out of their frustrated relations, but don’t quite realize this. The critic Michael Taylor references Hill’s essay and takes this further, arguing that the scene in which Imogen discovers Cloten’s headless body and mistakes it for Posthumus is a kind of purging of this sexual disturbance, an appropriately grotesque climax for a relationship marred by repression. He claims that this disturbance is lifted in the finale, and that the couple matures, at last ready to consummate their love.27

I find all this invalid — it sounds like something out of William Butler Yeats, and has little to do with Imogen. The same goes for the image of Imogen as a virgin martyr offered in Bamford’s essay. These are eloquent arguments, but we go back to Imogen and can’t find them. Imogen never seems involuntary, never merely a martyr or a victim. She is never reduced by her circumstances, and always recovers quickly. Her will is always strong, simple, and at the ready.

I do not think it provides much insight to see her as suffering from some kind of psychological darkness due to repression. She is certainly not sado-masochistic, although she may have a peculiar psychosexual profile that is hinted at when she says she would change her sex to be with her brothers. This is before she knows they are her brothers, when she first meets them and is disguised as a man. We do not know if she means she would become a man in order to join them as a man or if, already being disguised as a man, she means she would like to be a woman in their company. Bloom chooses the former and says she thus evades the charge of incestuous desire, but I think the ambiguity is hard to avoid, and is on purpose.28

She tells her father she chose Posthumus because they had grown up together. Cloten, though he comes later, is also her “brother,” through her father’s remarriage to the Queen. We might see Imogen as a sheltered girl who is used to the close company of boys. Miranda in The Tempest is similarly sheltered.

Taylor is right to emphasize the irony and grotesquery of the scene of Imogen embracing the headless body of Cloten. When she runs her hands along his body, mistaking it for Posthumus, I think Shakespeare is calling attention to her virginity (and to the arbitrariness of her choice of Posthumus), and might even be understood to be attempting to humiliate her. The whole “siege” of her virginity throughout the play might be seen this way. But I think we will not read her correctly until we see that Shakespeare has failed to humiliate her.

Gervinus is basically right about her, and Bloom is right about Posthumus. The correct reading of the play would merge these two views. This might seem like an impossible combination of tones, where Imogen is the most gorgeous of ideals and Posthumus an absurd mediocrity and a parody of Hamlet, but I think it is what Shakespeare intended.

Imogen says early in the play that she envies those who have their “honest wills.” This is far from Hamlet’s puzzled will, Iachimo’s “cloyed will,” and of course has nothing to do with Posthumus’s misogynist rant, when he says he hopes that promiscuous and dishonest women will “have their will,” spreading vice throughout the world.

Imogen might be said to be the cause of virtue in others, and the unwinding of the virtuoso plots around her is a demonstration of the supremacy of her will. The long concluding scene where all these plots are undone, where all the deception and misunderstanding comes to light and the wrongdoers are easily forgiven, represents this. It is the realization of what Iachimo witnessed all at once in the seduction scene, but refused to accept. What Imogen would have resolved at high speed has taken her corrupted companions five acts to come to terms with. She is the “harmless lightning” in Cymbeline’s phrase, and the rest of the characters are “crooked smoke.”

I do not accept discussions of Imogen having been worn out by the action of the play, like in Bamford or Granville-Barker.29 The predominant emotion in the end is relief, and Imogen confidently goes off alone with her father at the beginning of the scene. When Posthumus mistakenly throws her to the ground she forgives him right away, and responds with remarkable humor, strength, and eroticism. It is the same “conjugal tenderness” she had at the start.

With respect to Shakespeare’s body of work, her will is to do away with Hamlet and the tragedies. The advent of Imogen has made them obsolete. Unless we accept this we will remain incredulous, outraged that Shakespeare would discard even the phase of artistic achievement that gave us Hamlet and King Lear.

Posthumus does not have an audience like Hamlet does in Horatio, and he has no book to drown like Prospero does. The book of his life belongs to Jupiter, which Jupiter lays on his chest at the end of his dream. He is ultimately a tool of the gods, a tool of history, and a tool of Imogen’s desire. This is his strange fate — to be blessed with the favor of Imogen and Jupiter without the ability to transmute that favor into any deeper knowledge of himself. No action he could undertake, not even what I assume to be his dissipation in Italy after his misogynist soliloquy, delivers him any insight into himself. Iachimo’s fate is similar — he cannot overhear himself in his “charmed” soliloquy in front of Imogen, and though he is relieved to be forgiven in the end, he also seems baffled. It would seem that this earlier mode of Shakespearean self-knowledge has been rendered inaccessible.

Imogen is a miracle of feminine beauty and inner virtue combined with an imperious willpower — a rare being. In her play, there is nothing to be done but to surrender to her will, which is indeed not a painful matter at all.

Cover image credit: Folger Library Imaging Department

You can watch a low quality video of the BBC one on Internet Archive — https://archive.org/details/cymbeline_202404 — or a nicer one through the BritBox subscription on Amazon. The Dakota Johnson movie is on Netflix.

Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human by Harold Bloom. 1998. pp 623-624, and p. 628

Bloom is one of the best overall critics of Shakespeare, but he is so outraged by Cymbeline that I think at times he distorts the play.

Characters of Shakespeare’s Plays by William Hazlitt. 1817. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/5085/pg5085-images.html.

Hazlitt comes off surprisingly narrow-minded about Imogen, claiming she is only worthy of our interest because of her affection for Posthumus. George Fletcher is rightly indignant about this absurdly inadequate reading in his Studies of Shakespeare.

Jameson, Anna. Characteristics of Women: Moral, Poetical, and Historical, aka Shakespeare’s Heroines. 1832. p 195 and p 191.

Jameson has careful observations of personalities and tends to offer insights via comparison with other personalities, which is a more Shakespearean method than the approach of other critics.

A Study of Shakespeare by Algernon Charles Swinburne. 1920. p 227. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.93153/page/n237/mode/2up

Jameson, p 191

Fletcher, p 42-47

Fletcher, George. Studies of Shakespeare. 1843. p 43. https://archive.org/details/studiesshakespe00fletgoog/page/n70/mode/2up

Gervinus, Georg Gottfried, Shakespeare Commentaries, 1849-1852, trans. by F. E. Bunnett in 1863. p 658. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Shakespeare_Commentaries/NzM_AAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1

Gervinus has some of the best commentary on Imogen I could find, and goes the farthest in (I think rightfully) defending the greatness of the play and arguing for the depth of Imogen as a character. He is also the only critic I found who attempts a deeper reading of Pisanio’s personality, which I found convincing (p 673-674). I have not seen it remarked anywhere that in her disguise as the male servant Fidele, Imogen arguably imitates Pisanio, who is her closest friend.

His attempt to find a “moral” unity in the play is correct as a contemplation of Imogen’s personality and her effect on others, but I think it is misleading to claim that Shakespeare wants to suggest there is something metaphysical behind the play that agrees with this moral vision. In general, the numerous frustrated searches for “unity” by critics of Shakespeare — moral, metaphysical, allegorical, “formal,” etc. — would seem to be misguided.

Gervinus, p 659

“Cymbeline is the only play in the canon which has characters given to such tensely obscure ways of expressing themselves that not only the audience but the other characters find it hard to make out what they mean.” Shakespeare’s Final Plays by Frank Kermode, p 22.

Dr Johnson calls Iachimo’s performance in this scene “counterfeited rapture.” Frank Kermode calls it “hysterical virtuosity.”

In The Poetics of Jacobean Drama p 103-106, the scholar Coburn Freer claims (based on a stray remark earlier in the scene) that Iachimo’s complex speeches are meant to test Imogen’s intelligence. He claims that Iachimo’s obtuse performance is like a coded message to Imogen to see if she’ll understand that he’s trying to seduce her. If she doesn’t pick up on this, he can just claim the artificial rhetoric was all a performance and a test of her virtue (presumably the artificiality of the performance would be more believable as a false test). I find this to be a strained reading. Does Freer mean to say that Iachimo fails because Imogen is less than intelligent? Why would Iachimo suddenly be interested in Imogen’s intelligence? What does that have to do with seducing her? Freer admits it is a disastrous attempt at seduction, but he also wants us to believe that the experienced seducer Iachimo always maintains exquisite rhetorical control. This does not hold together. And, like many other critics, it does not account for the actual content of Iachimo’s speeches. The abstract wandering toward the cloyed will, the involuntary self-revelations, the chaos of metaphors and confused feelings, even the ugliness of much of the figurative language — what woman, of any intelligence, would be seduced by this?

Karen Bamford, “Imogen’s Wounded Chastity.” https://www.enotes.com/topics/cymbeline/criticism/cymbeline-vol-36/classical-allusions/karen-bamford-essay-date. Originally published in Essays in Theatre / Études Théâtrales, Vol. 12, No. 1, November, 1993, pp. 51-61.

This is an odd metaphor, especially in light of the Soothsayer’s vision at the end of the play, where an eagle vanishes into the light of the sun.

Dr. Johnson calls this a “poor conceit.” https://www.online-literature.com/samuel-johnson/shakespeare-tragedies/8/.

Bloom, Invention of the Human p 632

Hamlet: Poem Unlimited by Harold Bloom. The chapter “The Imposthume” is pp 67-71.

Bloom, Poem Unlimited, p 71

Bloom, Invention of the Human, p 636

Jameson, p 195-196

Harold Goddard. The Meaning of Shakespeare. 1951. p 249-50.

Gervinus, p 657

Bamford essay mentions disagreement on this point in footnote 3

Michael Taylor, “The Pastoral Reckoning in Cymbeline“, collected in the The Cambridge Shakespeare Library. 2003. p 438. https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780521808019_2/page/438/mode/2up.

Bamford essay

Geoffrey Hill, “‘The True Conduct of Human Judgment’”, collected in The Morality of Art. p 25. https://archive.org/details/moralityofart0000dwje/page/28/mode/2up.

Taylor, p 441

Bloom, Invention of the Human p 628

Granville-Barker’s chapter about Imogen has some good points though. He is unique in his recognition of Posthumus’s mediocrity and his easy forgiveness of him — “It will be hard for any dramatic hero to stand up, first to such praise as is lavished upon Posthumus before we see him (though when we do he is not given much time or change to disillusion us), next against the discredit of two scenes of befoolment, then against banishment from the action for something like a dozen scenes more. Nor in his absence are we let catch any lustrous reflections of him. Were he coming back, Othello-like, to do his murdering for himself, we might thrill to him a little. He is a victim both to the story and to the plan of its telling. Even when he reappears there is no weaving him into the inner thread of the action ... He can only soliloquize, have a dumb-show fight with Iachimo, a didactic talk with an anonymous “Lord” who has nothing to say in return, a bout of wit with a gaoler who has much the best of it; worst of all, he becomes the unconscious center of that jingling pageant of his deceased relatives--a most misguided attempt to restore interest in him, for we nourish a grudge against him for it.”

Granville-Barker, Harley. Prefaces to Shakespeare Vol 2, 1963. https://archive.org/details/prefacestoshakes0000gran_e0w6/page/n5/mode/2up. p 143

Thank you this wonderful essay on a play I did not know well. The discussion by Gervinus was of special interest.