T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land Sucks and It’s Only Getting Worse

T. S. Eliot’s masterpiece is a hundred years old, and it has never stopped spreading misery and death

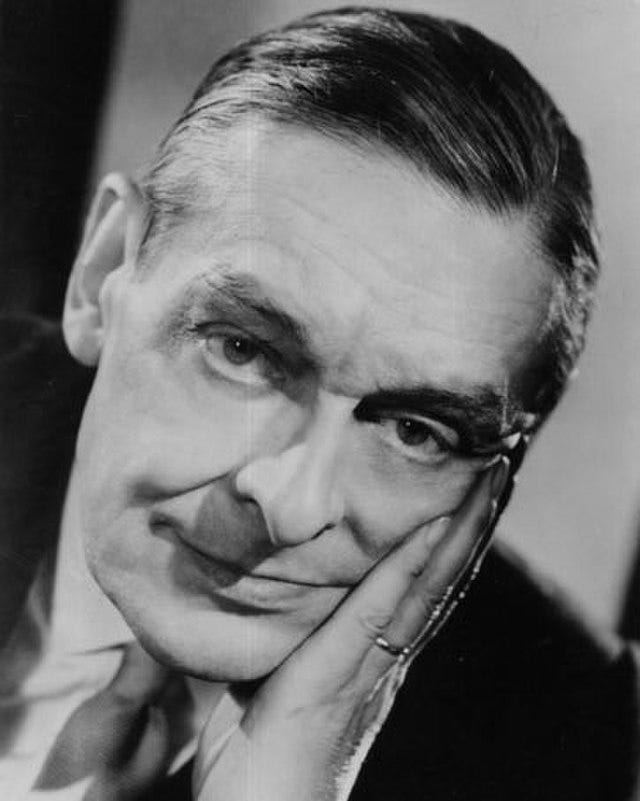

Hey, I know you’re bored, so here’s something for you: a New Yorker writer gushing about a hundred-year-old poem that was once so “modern” and now sounds very old, indeed makes me feel older every time I read it. The poem is called The Waste Land, and it’s by T. S. Eliot, who hated Missouri so much he decided to become pretend-English and have breakdowns. The breakdowns led to scribbling that his friend and avid scissor user Ezra Pound would cut up and then they published the stuff. When people read it, the death in them would sing out like a happy chorus, and pretty soon it was a whole “generation” in unison singing “yes yes yes, this is us, tell us more, we want to die”.

Paper being permanent as long they keep printing it, unfortunately, we have to keep hearing the death-call every time we open an anthology about the “twentieth century” and the poetry that was written “during” it. Now we are in the twenty-first — two decades into it — but everyone is so fearful and “historicized” that they find themselves hating the fact that any time has passed, and so cling to things like “centenaries” of “masterpieces”, which they clutch close to themselves like the fear they love so much.

The scene in the New Yorker piece is of a group of dyspeptic and miserable poetry readers making a May pilgrimage to somewhere in England, that wet crowded island where they speak too softly and don’t know the meaning of the word “forthright”. They would have preferred the event to have been in April, like the poem’s first line, “April is the cruellest month”, which would have made it more dour. But these people bring dour enough on their own, and weep at the reader at the lectern — someone named “Benedict Cumberbatch” — doing so much lovely justice to such an old musty poem.

“My, my,” they say, “this man captures it, the death I hold in my fragmented heart, yes, tell me more!”. They even get an undead academic afterwards to discourse upon how everyone is so very “fragmented” these days, and then they all get their smartphones out so they can shore up some fragments against their own ruin on “apps” run by “social media” companies, and when they’re done they look up and say: “Is someone writing a New Yorker piece about this? I hope so.”

The man writing the piece, who is there, raises his hand and says: “Yes, I am writing one, and this event is intriguing, though admittedly I’m reluctant about some of the experimental musical accompaniment at today’s festivities. It will be a relief when I show up at the 92nd Street Y to hear a reading of the poem all over again, with no music, so I can really feel the death in it better. It’s being done by — perhaps you’ve heard of him — Ralph Fiennes. Splendid.” “Well,” says the pretend-English audience back to him, “we’re looking forward to the piece.”

For Eliot, death goes hand-in-hand with concealing lasting love for velvety ladies, and so the New Yorker author takes a moment to tip his hat to Lyndall Gordon’s new biographical volume on Eliot’s “hidden muse”. Love is better when it’s dark and secret and shame-ridden, which makes it more “complex”, and so is sure to sell well. Yes, to the centenary, publishers are “paying heed”! Here come the capacious biographies based on “secreted” letters newly “unsealed”. Maybe he’ll even use the word “trove”, and it’ll be somewhere a little puzzling, like the University of Texas!!!

Actually, it’s at Princeton, which is not quite London but fine, good enough. Death will be a good cafeteria snack for the Princeton youngsters too, and maybe they’ll pick up a copy of Matthew Hollis’s The Waste Land: A Biography of a Poem, so they can read all about Eliot’s dreadful childhood, with “summers on the coast of Massachusetts”, God help us. He flees to Paris and London, much better, and marries Vivienne Haigh-Wood in 1915, a union of “incurable horror … rich in sickness on both sides”. The sad young couple in search of role models from the sacred past for their mutual morbid attachment need look no further! If in coitus you do not smile; if in your lovers you prefer stranded Italian-speaking mermaids weeping in the shadow of some old columns; if the thought of a European cup of coffee makes you sick with all the acid reflux it might bring — then this story is for you! These proclivities go well with a love of “textual information and commentaries”, which you can find on the new “Waste Land” app, which is “bristling” with them! No really, it’s real! The New Yorker author has it and, in a winning aside, says he likes it better than the version of Candy Crush he used to play in 2011!

Eliot is pretend-English, but it’s important we remember that he really was still an American when he wrote the poem. Americans keep forgetting, but, like, actually the poem is pretty damn American even though it’s about London Bridge!! This is an important point for a British writer like the New Yorker author to mention, given their country’s centuries-long grudge against the United States and their wish for it to never quite fully grow into its own culture. In The Waste Land they found the perfect psy-op, the masterpiece to convince America that theirs was a culture of death forever and ever. He brings in a big British favorite, Bob Dylan, to help him certify his American credentials, so, yes, thank you very much, keep going.

If you don’t like this, sorry, there’s no way out! He writes: “You may not know “The Waste Land,” and you may not like it if you do. But it knows you.”

Unlike, say, the infant Jesus Christ, the poem was first published to “no fanfare”, in the quarterly journal The Criterion alongside an essay about James Joyce and, appropriately, another essay by an “aged British critic titled … ‘Dullness’”. Eliot was the “begetter” of said periodical, which he created for the purpose of spreading Dullness, and through it he “held sway over … whole shires of the cultural domain”, his ponderous commentaries as Editor being “an august and regular feature”.

This author’s use of the word “shire” here is again proof of his imperial impulses, and so the whole conspiracy is revealed in a quick phrase. To you it may mean where the Hobbits come from, but to a visitor to dictionary.com it’s simply “one of the counties of Great Britain”. The whole global “cultural domain”, then, is a bunch of shires for Eliot, and so really is just a big zone of Waste Lands. Proper for this projectionist of morbid self-destruction, par for the course.

Eliot stuck the Great Work somewhere in the middle of his Q3 1922 issue of The Criterion, but no one knew how masterful a masterpiece it was then. It was kinda weird looking, and “Parts of it didn’t look, or sound, or feel, like poetry at all”. The author does not allow for the point that if it didn’t look or sound or feel like poetry “at all” then perhaps it was not poetry, but that doesn’t matter. Imagine that you’re a reader — no! a “bookish reader”, and it’s 1922. You are likely a bigot, and America just seems kinda loud and noisy over there across the Atlantic and you’ve never had luck in love. All your relationships keep ending with you holding dead bouquets on streets once walked on by Baudelaire and you’re a banker with loose pants who keeps shaking everyone’s hands and quietly smiling to yourself about how nasty the whole world is, while your ex-girlfriend is left weeping so long at home that she forgets to eat. What would you have made of the poem?

You’d be tickled by the French in there, which as we know is the right and proper language of the educated. I went to college and took classes in the major called English, the language I speak and write in, and we did the right thing and learned how to read it from Parisian eminences likes Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, Roland Barthes, and Lacan, the other Jacques. I still get so tickled whenever I think of these guys, they really did me a solid, and set me straight with a strong dose of this thing they called Theory, which they served ice cold, in a red Solo cup. I could quote to my heart’s content their lofty intricacies while tossing a ping pong ball across a table and then I’d take a break to chug beer. It did me and everyone in the room a lot of good to hear what these men had to say. It’s too bad Eliot couldn’t have been there, but that’s “history” for you, I guess.

While you’re getting tickled by the French, you might get more excited by a line in the poem, which I’ll quote now:

Jug jug jug jug jug jug

Our man at the New Yorker assumes this must mean something feminine, so alright, great, you too like the “flavor of smutty Elizabethan slang”. Keep going.

But wait! It’s not 1922! It’s 2022! A hundred years have gone by! You’re definitely NOT a bigot now, but you’re not “bookish” anymore, just “ordinary”, which is British for “loser”. You have “no classical education, no French, and no access to opera”, and so you close the book dismissively. Your fucking loss.

But it doesn’t matter, “Escape is useless”. Everybody, after all, has “memories draped by the beneficent spider” or has put things “under seals broken by the lean solicitor”. We all have that friend named Marie, “of aristocratic descent”, whom we once heard recall “an episode from her girlhood”, or a girlfriend who brushed her hair while complaining of bad nerves. We’ve all been blind seers who watch “two loveless urban dwellers making love”. We’ve all gone “fishing in the dull canal”.

You’ll get taken in by all this, just like everyone else, and will need to go buy up volumes of John Webster and Thomas Middleton so you can get all the wily references. Eliot is Really Helpful in the notes, where he points you to things like “Ezekiel, II, i” and something called The Tempest.

He really does have a love of webby references — kinda feels like reading Wikipedia or something! He goes from Dante to Sherlock Holmes in just a few lines! This is of course one of his ploys in his quest to become pretend-English, and it’s helpful that the New Yorker author illuminates this obscurity. In a story about a key turning in a lock, Sherlock hears a key turning in the lock — aha! — just like a line in the poem. Even better, there’s a different poem that Eliot wrote later, after he got really into the pope and stuff, where he has a line that’s like “Hey, are you coming?” and it’s pretty close to a similar “urgent question” in a Sherlock tale!! Eliot received the Order of Merit in 1948, and it’s easy to see why.

Sing them out, those “adamantine lines” destined for fame across the centuries, about how a guy “foresuffered all / Enacted on this same divan or bed” !! I can personally attest that I had several enactments on divans or beds that I had foresuffered but simply couldn’t make sense of until I got to Eliot, and so I’m grateful.

The same can’t be said for an employee of a moving company the author once had the misfortune of working with, who after moving all the man’s books out of his house said: “If I never see another book on T. S. Eliot, it’ll be too soon.” This philistine of course has been proven wrong by the invincible immortality of Eliot’s ever-expanding death-machine and its accompanying “secondary and tertiary literature”, which has “swelled beyond reckoning”.

Anyway, one wonders how they get on with that thing called “communicating” across the pond, everyone’s ironic tones being so inscrutable. They all seem to be in the parlor of a Jane Austen novel winking to a wise aunt who’s come to visit. Mr. So-and-so has come over and he’s just a bore, but you can’t say that. But the wise aunt understands, with a silent look and a wry half-smile. All this is very good, but what happens when everyone has their own separate wise aunt? Won’t things get a little lost? Take, for example, Virginia Woolf’s response after she first heard Eliot’s godlike verses, which our New Yorker man quotes:

Eliot dined last Sunday & read his poem. He sang it & chanted it & rhythmed it. It has great beauty & force of phrase: symmetry; & tensity. What connects it together, I’m not so sure.

And then:

One was left, however, with some strong emotion.

For whose aunt is such mute irony? How to put the puzzles pieces together? Figuring out England starts to feel a bit like reading The Waste Land, where everyone is their own quizzical fragment and, for whatever reason, it seems like in order to understand them we need to be sent to some boarding school somewhere where we get caned or something like that, and then we all come out more humorous.

This strange instinct of mine was confirmed by the author’s subsequent digression into his fascination with Eliot’s love of the “Rollo” books, which are about a particular dry mouthed boy named Rollo who, it seems, spends his time preparing for a writing life filled with “doleful invocations” by developing something he calls “Rollo’s philosophy”, in a written work with subtitles like “Water,” “Air,” “Fire,” and “Sky.” I thought at first that the author was going to mention something about Avatar: The Last Airbender, which is a children’s show I like about the elements, but then I reasoned that it wouldn’t make sense to have both “Air” and “Sky”, with “Earth” missing. This question was never cleared up for me, but the author helpfully points out that these subtitles are later repurposed in a poem by Eliot about death, where he lists things like the “death of air” and the “death of water”.

Then the author quotes some tantalizing Rollo passages from a chapter momentously titled “Who Knows Best, a Little Boy or His Father?”. Rollo’s father favors “Biblical broadsides” like these:

“Your heart is in a very wicked state. You are under the dominion of some of the worst of feelings; you are self-conceited, ungrateful, undutiful, unjust, selfish, and,” he added in a lower and more solemn tone, “even impious.”

I added the emphasis here at the end myself and was imagining a skilled actor intoning these words. It gets confusing from there, as Rollo’s cousin wants it to rain but Rollo doesn’t, and Rollo’s dad makes this into an elaborate metaphor to scold him. At first I was tempted to put Rollo’s dad in the Dickens villain bucket, but then there’s something about his scolding that promises some penitence from young Rollo, and penitence for sin is important, and so the author finally gets to his point. Dryness is sin and wetness is redemption, and in The Waste Land Eliot spread his sin to the whole world. I think there are some follow-up poems or some more “hidden muses” or something like that that promise redemption.

At the end of things, “Benedict Cumberbatch” finally finishes up his recitation and the author quizzes a philistine woman in the crowd who happens to be “unencumbered” by having read Eliot before on what “struck her most” about the poem:

“The landscapes,” she said, without hesitation. “The rocks and the rivers. All that dryness.”

Blah blah, something about a Sibyl!! Who tells us in each “era” — like for example the current one — “whatever it is that we most fear to hear” !!

I will say then what you most fear — that The Waste Land is a relic, trash writing, a ruin of a bygone century that did no one any good and still doesn’t. Its passing into its hundred-year-old birthday and our happy celebrating of it only shows how desiccated we are — the world one big army of Rollos, praying the rain won’t come.

Leave Benedict Cumberbatch alone!

Sarcasm can make anything seem bad. This piece is funny and dynamic, but I'm not sure whether it has any depth. Personally, I love Eliot without needing to understand his references or assimilate his views on poetry or the world. The Waste Land's dour, sibylline character, like a nightmare in tongues, pleases me to no end--though I have always preferred Prufrock or the Four Quartets precisely because they are less inkhornishly modernist. I can understand your vitriol in response to the goggle-eyed praise lavished upon Eliot, but many people have been deeply moved by The Waste Land for reasons other than shoring up their own pretentiousness against the ruin wrought by common sense...